THE LAST MAN TO DIE

80 years ago, Robert Capa photographed 'the last man to die'. Here, Capa and an eyewitness discuss the iconic image.

As the Allies advanced through the heart of Germany in April 1945, eighty years ago, they discovered a charnel house of suffering and horror. On 15 April, the British liberated Belsen. Though 31-year-old Robert Capa could have joined reporters such as Edward Murrow and Martha Gellhorn in recording the liberation of other camps, the Twentieth Century’s greatest combat photographer chose not to. “The [camps] were swarming with photographers,” he explained, “and every new picture of horror served only to diminish the total effect. Now, for a short day, everyone will see what happened to those poor devils in those camps; tomorrow, very few will care what happens to them in the future.”

There was one story Capa did want to cover - the liberation of Leipzig. In a radio report, Edward Murrow described what “strategic bombing” had done to the hometown of Gerda Taro, the great love of Capa’s life who had been killed during the Spanish Civil War: “The shelling had caused no fire. There was nothing left to burn. It was merely a dusty, uneven desert."

Amid the desolation, Capa exposed his last rolls of the war.

On 18 April, as Germans surrendered in tens of thousands throughout the remnants of the Third Reich, he joined the US 2nd Infantry Division as it approached the Zeppelin Bridge over the Weisse Elster Canal.

Capa explained in a 1947 radio interview – the only recording of his voice that has ever been found - how he then came to take the most poignant photograph of his career: “It was obvious that the war was just about over, because we knew the Russians were already in Berlin [sic] and that we had to stop shortly after taking Leipzig. We got into Leipzig after a fight, and just had to cross one more bridge.”

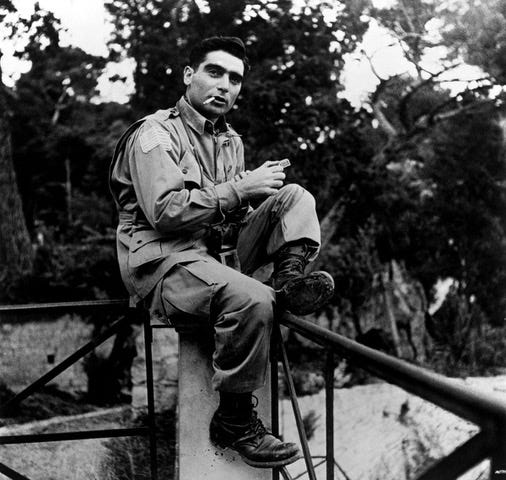

“The Germans put up some resistance so we couldn't cross. There was a big apartment building that overlooked the bridge. So I figured, “I'm going to get up on the last floor and maybe I'll get a nice picture of Leipzig in the last minute of the fight.” I got in a nice bourgeois apartment where there was a nice young man on the balcony - a young sergeant who was [setting up] a heavy machine-gun. I took a picture of him. But, God, the war was over. Who wanted to see one more picture of somebody shooting? We had been doing that same picture now for four years and everybody wanted something different, and by the time this picture would have reached New York probably the headline would be “peace”.”

The man in question was 21-year-old Raymond Bowman, the fifth of seven children, from Rochester, New York. He had entered the apartment with fellow machine gunner Lehman Riggs. The pair belonged to Company D of the 23rd Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Infantry Division.

In an interview in 2020, Riggs told me: “Robert Capa was with us. We had taken half of the city, and we came to a huge man-made canal, and there were bridges every two to three blocks. We were ordered to go up on the third floor of this apartment building to try to keep the enemy pinned down as men crossed the bridge. That’s when it occurred. There was a sniper that got my buddy, right beside of me.”

It was 3.15pm when the shot rang out, hitting Bowman in the head and killing him instantly.

In his 1947 radio interview, Capa described how Bowman “looked so clean-cut like it was the first day of the war and he was very earnest. So I said, “All right, this will be my last picture of the war.” And I put my camera up and took a portrait shot of him and while I shot my portrait of him he was killed by a sniper. It was a very clean and somehow a very beautiful death, and I think that's what I remember most from this war.”

Riggs, a retired postal worker, made a pilgrimage back to Europe in 2016 and actually visited the apartment where his friend had been killed. According to Riggs: “The event had so disturbed my mind because of the loss of my buddy, I had tried to block it, and hadn’t talked about it for years. But returning to the scene unlocked all the memories… I was 3ft from him when it happened. I could have reached out and touched him, but I knew he was dead. I had to carry on in his place, as I’d been trained to do.”

Riggs knew he had been very lucky. “I had just been firing the gun, and I just stepped back off the gun and he had taken over… I happened to look up and see the bullet pierce his nose. The bullet that hit him killed him, ricocheted around the room, and it’s a miracle that it didn’t hit me. As soon as he got hit, somebody had to take the gun. I had to jump over him and start firing the gun.”

When Riggs returned home after the war, he opened a copy of Life magazine, which his wife had bought, and first saw Capa’s images. It was as if he was back in Leipzig, reliving what had happened that cold day so close to the end.

Capa would never forget Bowman’s death either.

“And that was the last - you think - probably the last man killed during the official war?” asked Capa's interviewer in 1947.

“That's right,” Capa replied. “I'm sure that there were many last men who were killed. But he was the last man maybe in our sector.”

“It was certainly a picture of the uselessness of the war,” said Capa's interviewer.

“Very much so,” agreed Capa. “It was certainly a picture to remember because I knew that the day after, people will begin to forget.”

Capa did not tell his interviewer what happened after he took his shot of the “last man”. In his next frame, Bowman lay slumped on the floor, blood flowing from his neck. For long seconds, Capa shot the pool of blood as it seeped toward him.

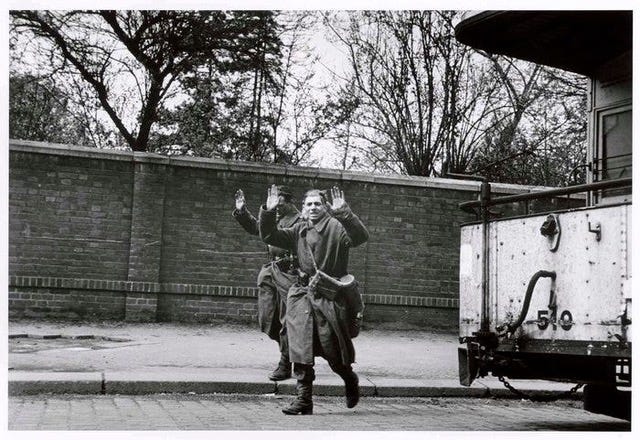

According to Life, the “other members of the platoon [then] decided to find where the fatal shot had come from. Stealthily, they single-filed onto the cobblestone street and surrounded Germans barricaded in several abandoned streetcars. They fired a few warning shots. Presently two Germans came out with their hands up shouting, "Kamerad!" The Americans, feeling no elation, took them away.”

The war in Europe ended just a few weeks later on 7 May 1945.

In 1954, Robert Capa was killed in Vietnam, aged just forty, after stepping on a landmine.

On 17 January 2021, Lehman Riggs turned 101. He passed away the following August. When I last spoke to him, he told me Capa’s images still haunted him. They were forever etched in his memory - a black-and-white record of those fateful seconds 80 years ago when he watched his buddy become “the last man to die”.

Please see this special film about Riggs and Capa and share.

Click here.

This post is part of an ongoing monthly series for Friends of the National WWII Memorial. Please support Friends here

https://www.wwiimemorialfriends.org/our-mission

uselessness of war. burning jnto my brain.

First photojournalist to die in Vietnam in'54. His documentation is so valuable; a true hero.