THE FIRST FLAG

80 years ago, two Red Army soldiers planted the Hammer and Sickle above the Reichstag, signifying the defeat of Nazi Germany. This is their amazing story.

THE FIRST FLAG

80 years ago today, two Red Army soldiers made history—they planted the Hammer and Sickle above the Reichstag. Yet their act has been forgotten because the Germans soon shot down their flag, and there was no photographer present. On 2 May, another flag was placed atop the Reichstag; the photo of this event is one of the most iconic in history, signifying the defeat of Nazi Germany.

This iconic image was taken on 2 May. However, the first flag was placed atop the Reichstag on 30 April.

Here is Lt. Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev’s amazing account of the planting the first flag:

“April 30, 1945… It was still dark between four and five in the morning. Shells and land mines exploding and tanks roaring all around. Heavy smoke and dust covered the streets. Moving forward was hard.

Getting inside the building [The Third Reich’s Ministry of Internal Affairs] was impossible because of the enemy’s continuous machine-gun fire. The advance stopped for a while. We lay in wait.

The tankers saved the situation. With a few heavy strikes, they breached one of the walls. We used that opening to open fire.

It’s hard to describe what our warriors felt at that moment when we had only taken control of a single room in an eight-story building—it was just the first step towards performing the mission…

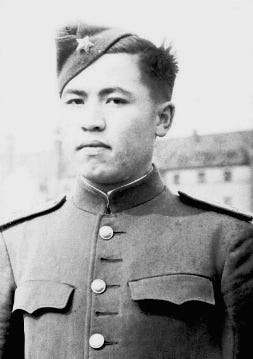

Lt. Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev in 1945.

Before the other troops arrived, we were delivering continuous fire through an open door, lobbing grenades to the enemy through windows and staircase doors…

There was a battle for every room, for every floor.

Despite the grim resistance from Hitler’s soldiers, as soon as the rest of the troops arrived, our advance strengthened. There was a battle for every room and every floor. In some areas, hand-to-hand combat ensued. Gradually, the fighting moved to the second floor.

The dawn was breaking. The area we had taken over expanded significantly. We needed a lot of ammunition, especially grenades, to clear the entire building of the Nazis. As we always did in such situations, we fought the enemy using their own munitions, which were stored abundantly in the same building.

By noon, some of the troops had reached the fourth floor, and my platoon was among them.

I would like to mention the names of my platoon’s warriors who particularly distinguished themselves in that battle: Senior Sergeant Nikolay Goncharov awarded the Order of the Red Banner [posthumously], Private Grichko awarded the Order of the Red Star. Bravery and gallantry they demonstrated in the battle set the example for everyone.

During the battle, I was informed that the battalion commander had called for me. I had left Nikolay Goncharov [who died by the end of the day] in charge and went down to the first floor to meet the commander, reporting my arrival. [He] huddled against both sides of the wall due to the continuous machine-gun fire coming through the broken window from the buildings across the street.

The commander said, “The moment the hostile fire pauses, quickly look at the square outside the window. That big grey building with a dome you will see there — that is the Reichstag.” After a pause, he continued, “At the moment, our battalion is the closest one to the Reichstag. So the aim is as follows: make the way to it as soon as possible and mount the red flag. Upon the recommendation of comrade Vasilchenko, I called on you to accomplish this task. And I must warn you that this is not a command. Think it over and decide yourself. While gaining the ground you will be backed up by the fire of our reconnaissance men who arrived from the headquarters for this purpose.”

When the commander said that I had been called upon Vasilchenko’s recommendation, I looked up at that aged silver-haired man, all covered with dust, with a rifle hanging on his neck. He was looking at me and waiting for me to respond…

We waited until the fire paused, I jumped out of the window and lay down in a shell hole. There was only Bulatov next to me. “Comrade lieutenant,” he said, “the other reconnoiters could not jump. Fire. We’re lucky — we got through.”

I told Bulatov that we were going to creep, one behind another. Machine guns were heavily firing from each side, so we could not even raise our heads. We were slowly creeping, right after each other.

When we creeped out of the shell hole, the only cover ahead were the iron beams stowed nearby. Upon reaching them, we got our act together and quickly got the lay of the land. The next cover could be the transformer box 40-50 meters away from us.

Bulatov is at the front of the picture.

The square was too exposed—nowhere to hide. Just that box. The journey to the box was hard and exhausting. Just imagine: landmines exploding everywhere, bullets buzzing, my face almost touching the ground, unable to move my head—otherwise it would be noticed. We were moving so slowly that one could hardly tell we were alive. Finally, we reached the box. Our clothes were soaked with sweat. The box was wood-framed and full of holes from a hail of bullets. It was too dangerous to stay there any longer. Besides, we could easily come under the fire of our own troops, because no one knew about us except our battalion. This forced me to make a quick decision. There was a minute to inspect the field: a broken iron bridge lay between the Reichstag and us, about a hundred meters away. But again, there was a flat, exposed square leading that way.

1.5 million Soviet troops fought in the Battle of Berlin.

Second half of the day. Our spotter planes began to appear above us more frequently. Just after they departed, a massive artillery barrage rained down on the park and the Reichstag. Heavy gunfire and explosions sent plumes of black smoke, fire, and dust over the square.

We could not wait any longer. We took a risk. Sprang to our feet, we blasted towards the bridge as fast as we could. It was really interesting to recall afterwards that while running, we took each other by the hand. We noticed only at the moment we reached the bridge and fell right into the water.

The channel was shallow. Despite the bullets whistling all around, for the first time on that day, we looked into each other’s eyes and smiled unintentionally.

I took out the red flag, unfolded it, and with an ink pencil wrote our unit number in the corner — 674, along with our surnames: Bulatov, Koshkarbayev.

The Red Army troops suffered enormous casualties to take Berlin, almost a million by some accounts.

Because of the danger, we had to relocate to the opposite side of the channel. Now we are about three hundred meters from the Reichstag… The fire is becoming more intense along the shores on both sides. Forging ahead is impossible. Twenty to thirty minutes passed. We’re still not moving. I took out the red flag, unfolded it, and with an ink pencil, wrote the number of our unit in the corner — 674, and our surnames: Bulatov, Koshkarbayev. Bulatov watched me write and then said, “It’s good that you wrote that, comrade Lieutenant. We might get killed and no one will even know who we were and where we came from.”

“Go, run!”, I said to him.

We didn’t see or hear anything; we were just running ahead. We reached the first steps of the front entrance to the Reichstag. Huddled together, we held our breath for a moment. After a minute-long silence, I remembered we needed to plant a flag in a well-visible place. We were so happy that we could not even think of the dome. I helped Bulatov sit on my shoulder and lifted him to the railings near the window. “Grisha,” I said, “mount the flag as high as possible.”

He replied, “There’s nothing to attach it to. Hold me a little longer — I will take a brick from the window.”

A minute later Bulatov exhaled huskily, “Done! I PUT IT.”

Ever since then, April 30 has been my second birthday. Every year on this day, I feel a special joy. Those hours of struggle and happiness are unforgettable.”

Lt. Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev died in 1988.

The ruins of the Third Reich.

Lt. Rakhimzhan Koshkarbayev after the war.

The debt that the world owes to the Red Army is too great ever to be repaid or acknowledged.

Thank you for putting agave on the Ted Army. Russia lost 20% of her population in World War II.