5 JUNE 1944

The clock in the war room at Southwick House showed 4 A.M. The nine men gathered in the twenty-five-by-fifty-foot former library, its walls lined with empty bookshelves, anxiously sipped cups of coffee, their minds focused on the Allies’ most critical decision of World War II. Outside, a gale howled, with angry rain lashing against the windows. “The weather was terrible,” recalled fifty-three-year-old Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower. “Southwick House was shaking. Oh, it was really storming.” Given the atrocious conditions, would Eisenhower give the final go-ahead or postpone? He had left it until now, the very last possible moment, to decide whether to launch the greatest invasion in history.

Ike and his staff at his camp near Southwick House in early June 1944.

Seated before Eisenhower in upholstered chairs at a long table covered with a green cloth were the commanders of Overlord: the no-nonsense Missourian, General Omar Bradley, commander of U.S. ground forces; Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, the overall commander of Allied forces on D-Day, who was casually dressed in his trademark roll-top sweater and corduroy slacks; Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsey, the naval commander who orchestrated the “miracle of Dunkirk”—the evacuation of more than 300,000 troops from France in May of 1940; the pipe-smoking Air Chief Arthur Tedder, also British; Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, whose blunt pessimism had caused Eisenhower considerable anguish; and Major General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff.

A tall and serious Scotsman, forty-three-year-old Group Captain James Stagg, Eisenhower’s chief meteorologist, entered the library and stood on the polished wood floor before Overlord’s commanders. He had briefed Eisenhower and his generals every twelve hours, predicting the storm that rattled the library windows, which had already caused Eisenhower to postpone the invasion from June 5 to June 6. Then, to Eisenhower’s great relief, he forecasted that there would, as he put it with a slight smile, “be rather fair conditions” beginning that afternoon and lasting for thirty-six hours.

The map room at Southwick House, scene of one of the most important decisions of the 20th Century.

Once more, Stagg gave an update. The storm would indeed start to abate later that day.

Eisenhower got to his feet and began to pace back and forth, hands clasped behind him, chin resting on his chest, tension etched on his face.

What if Stagg was wrong? The consequences would be unbearable. However, postponing again would mean losing secrecy. Moreover, the logistics of personnel and supplies, along with the tides, meant that another attempt couldn’t be made for weeks, giving the Germans more time to strengthen their already formidable coastal defenses.

Since January, when he arrived in England to command Overlord, Eisenhower had been under crushing and increasingly greater strain. Now it all came down to this decision. Eisenhower alone—not Roosevelt, not Churchill—had the authority to give the final command to go, to “enter the continent of Europe,” as his orders from on high had stated, and “undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces.” He alone could pull the trigger.

Eisenhower’s famous note, in which he assumes full responsibility if D-Day fails. He wrote it on 5 June, not 5 July, and found it in his tunic pocket weeks after the invasion.

Leading the largest invasion in military history was, at times, as terrifying as the very real prospect of failure. The last successful cross-Channel attack took place in 1066, nearly a millennium ago. The scale of this operation was nearly impossible to grasp. More than 700,000 individual items were necessary to launch the attack. Dismissed by some British officers as merely a “coordinator, a good mixer,” the blue-eyed Eisenhower, known for his wide grin and easy charm, nonetheless imposed his will, working eighteen-hour days, reviewing and adjusting plans to deploy approximately seven thousand vessels, twelve thousand planes, and 160,000 troops to hostile shores.

Eisenhower had overseen critical changes to the Overlord plan. A third more troops were added to the invasion forces, of whom fewer than 15 percent had actually experienced combat. Responding to General Montgomery’s concerns, Eisenhower ensured that the front was widened to nearly sixty miles of coast, with a beach code-named Utah included at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula, the westernmost point. It was agreed, after Eisenhower carefully managed the “bunch of prima donnas,” most of them British, who made up his high command—the men gathered now before him—that the night attack should benefit from the rays of a late-rising moon.

Rangers leaving for Normandy on 4th June 1944.

In addition, it was decided that the first wave of seaborne troops would land at low tide to avoid being torn apart by beach obstacles. An elaborate campaign of counterintelligence and outright deception, Operation Fortitude, had kept the Germans guessing about where and when the Allies would land, providing the critical element of surprise. Erwin Rommel, the field marshal in charge of German forces in Normandy, had not succeeded in fortifying the coast to the extent that he demanded. The Allies’ greatest advantage—their overwhelming superiority in air power—would make all the difference.

Not even Eisenhower was confident of success. “We are not merely risking a tactical defeat,” he had recently confided to an old friend back in Washington. “We are putting the whole works on one number . . .” Among Eisenhower’s senior generals, even now, at the eleventh hour, there was hardly any optimism.

Still pacing, Eisenhower thrust his chin toward Montgomery. He was fully committed to going. So was Tedder. Leigh-Mallory, ever cautious, believed the heavy cloud cover might prove disastrous.

Stagg left the library, passing through a cloud of pipe and cigarette smoke. An intense silence enveloped the room; each man understood how significant this moment was in history. The stakes could not be higher. There was no plan B. Barbarism, unprecedented genocide, the enslavement of tens of millions of Europeans: Nazism and all its associated evils might still prevail. The one man in the room whom Eisenhower genuinely liked, Omar Bradley, believed that Overlord was Hitler’s “greatest danger and his greatest opportunity.” If the Overlord forces could be repulsed and trounced decisively on the beaches, Hitler knew it would be a very long time indeed before the Allies tried again—if ever.

Six weeks earlier, V Corps commander General Leonard Gerow had written to Eisenhower, expressing serious doubts, even though it was too late to significantly alter the overall Overlord plan. It became distressingly clear after the 4th Division lost an astonishing 749 men—killed in a single practice exercise on April 28 at Slapton Sands—that the Royal Navy and American troops were not effectively coordinating. In addition to the disturbingly chaotic practice landings—the dismal yet final dress rehearsals—the defensive obstacles placed along the beaches in Normandy were particularly troubling.

Eisenhower wishing 101st Airborne troops good luck on 5th June 1944.

Eisenhower had chastised Gerow for his skepticism. Gerow had retorted that he was not being “pessimistic” but simply “realistic.” And what about the ten missing officers from the disaster at Slapton Sands who possessed detailed knowledge of the D-Day operations, the most significant secret in modern history? They were aware of “Hobart’s Funnies,” the collection of tanks specifically designed to penetrate Rommel’s defenses—including flail tanks that cleared mines with chains and DUKWs, the six-wheeled amphibious trucks that would take Rangers to within yards of the steep Norman cliffs—and they were fully informed about where and when the Allies were landing. Was it really credible to assume that the Germans hadn’t been informed, that so many thousands of planes and ships had gone unnoticed?

Even Winston Churchill, usually so ebullient and optimistic, was filled with misgivings, having cautioned Eisenhower to “take care that the waves do not become red with the blood of American and British youth.” The Prime Minister had recently informed a senior Pentagon official, John J. McCloy, that it would have been better to have had “Turkey on our side, the Danube under threat as well as Norway cleaned up before we undertook [Overlord].” British Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff, had fought in Normandy in 1940 before the British Expeditionary Force’s narrow escape at Dunkirk. Just a few hours earlier, he had noted in his diary that he was “very uneasy about the whole operation. At the best, it will fall so very, very far short of the expectation of the bulk of the people, namely all those who know nothing about its difficulties. At the worst, it may well be the most ghastly disaster of the whole war!”

Men of the US First Infantry Division land on Omaha Beach on D Day. Over 900 Americans died on Omaha.

No wonder Eisenhower complained of a constant ringing in his right ear. He was nearly frantic from nervous exhaustion, yet he dared not show it as he continued to pace back and forth, lost in thought, listening to the crackle and hiss of logs burning in the fireplace. He could not betray his true feelings, his dread and anxiety.

The minute hand on the clock moved slowly, lasting as long as five minutes according to one account. Walter Bedell Smith recalled, “I never realized before the loneliness and isolation of a commander at a time when such a momentous decision has to be taken, with the full knowledge that failure or success rests on his judgment alone.”

Eisenhower finally stopped pacing and then looked calmly at his lieutenants.

“OK. We’ll go.”

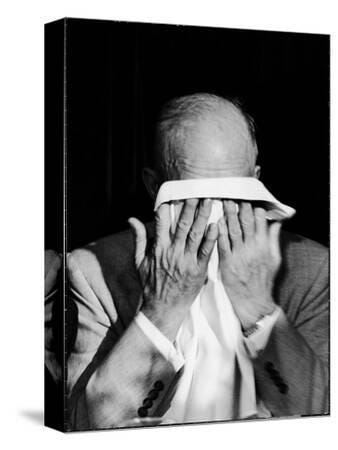

Eisenhower broke down in tears in 1952 when asked about the men he sent to their deaths on D Day.

Please obtain my book, The First Wave:

https://www.amazon.com/First-Wave-D-Day-Warriors-Victory/dp/045149007X/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0

The politics of the invasion were touched on in this post, but were significant. Stalin wanted a second front opened in Europe, and was unhappy with the strategy of attacking Sicily/Italy before France. Politics among generals. Marshall wanted Ike's job, but FDR wouldn't give it to him because he wanted him in the US. As Kershaw excellently describes, the amount of pressure everywhere on this decision was significant.

As Kershaw also relays, there are probably very few decisions in the rest of the 20th, or 21st century that rival it.

#salute #respect