"IT AIN'T TOO BAD"

Today was the happiest of WWII for Louis Kalil and thousands of Allied troops in Stalag XI-B, the first POW camp in Nazi Germany to be liberated.

Today, 16 April, was the most joyous of WWII for a starving rag-tag group of Allied soldiers – inmates of Stalag XI-B, the first POW camp to be liberated that most dramatic of springs in 1945. Sixteen nationalities were among the men set free, some of them having spent five long years in captivity.

One of those overcome with emotion today was Louis Kalil, a member of WWII’s most decorated US platoon. He and seventeen others in his unit had been taken prisoner on 16 December 1944, having fought ferociously to stop the spearhead of Hitler’s last desperate gamble in the Ardennes in December 1944 – the Battle of the Bulge.

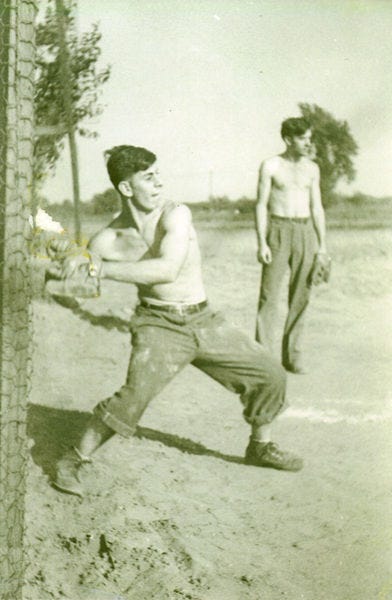

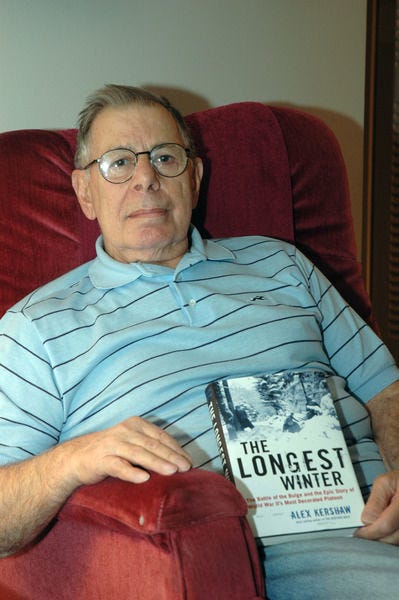

In an old box in a cupboard I found a battered tape recording from a 2003 interview I did with Kalil, an Indiana native, who was the last living survivor of the platoon when he died, aged 94, in 2017. It was a miracle that he survived the war to live so long, to be happily married for 63 years.

I’ve grown accustomed, sadly, to veterans I’ve known well dying almost every week in the last few years – they cannot defy age when they enter their late nineties. Some you mourn more than others and Louis was among the most self-effacing and inspirational of them all, stoic, modest, as tough as they come.

I decided to listen to Louis tell me his story again. His voice brought back vivid memories - of being much younger, less jaded, more hopeful, of jetting around the United States to track down eleven men from the platoon who were still alive during my research for what would become my most successful book, The Longest Winter.

Louis was calm and laconic as he told me his story. This morning, I found it just as moving as when I first heard it in his living room in a snowbound Indiana back in 2003.

Here are a few highlights…

It was around 11 am on 16 December 1944 in the Ardennes, three hours after first being attacked, when 22-year-old Private Louis Kalil noticed that German paratroopers were trying to infiltrate through woods to either side of his dugout.

A few feet from Kalil, Sergeant George Redmond was squinting through the sights of his M-1. To the left of their dugout, a German paratrooper crawled along the rock-hard ground. He got to within thirty yards of Kalil and Redmond and then quickly aimed his rifle, loaded with a grenade, and fired.

It was a superb shot. The grenade entered the dugout through its eighteen-inch slit and hit Kalil square in the jaw. But it did not explode. Instead, it knocked Kalil across the dugout to Redmond’s side.

Kalil was half-stunned as he lay sprawled on the base of the dugout. Redmond dropped his rifle, grabbed some snow, and rubbed it in Kalil’s face. Blood gushed from Kalil’s jaw. The force of the impact had forced his lower teeth into the roof of his mouth, where several were now deeply embedded. His jaw was fractured in three places. Redmond sprinkled sulfa powder on the wound and then pulled gauze out of both their first aid kits and started to wrap Kalil’s face.

There was no morphine in the kits to kill the pain. Once the shock wore off, Kalil would be in agony.

“How bad is it?” asked Kalil.

“Oh, it’s not too bad, Louis,” said Redmond.

“But I’ve got blood all over myself. It can’t be very nice.”

“It ain’t too bad.”

“Okay, I’ll take your word for it.”

Kalil knew Redmond was trying to make the wound sound a lot less severe than it really was. He could feel the teeth embedded in the roof of his mouth cutting into his tongue.

The battle still raged. Small-arms fire sounded like radio static during an electrical storm, a constant ear-piercing crackle. Redmond’s fingers did not shake despite his fear as he wrapped the last of the gauze around Kalil’s jaw. He knew the Germans could penetrate their position any moment. If they were to stand a chance, they would need to return to firing as soon as possible.

Redmond tied the last gauze bandage and met Kalil’s gaze.

“Don’t worry about it,” reassured Redmond.

“If things get to where you can take off, then take off,” Kalil replied.

Redmond looked at Kalil fiercely.

“We’re staying here— together.”

“Alright.”

Redmond grabbed his M-1 and began to fire.

Kalil was now in terrible pain but did the same, aiming with the use of just one eye at the figures that still approached up the bloodied hillside. It was so cold in the dugout that Kalil could feel blood freezing to his face, stemming the flow from the wound. The damned cold had been good for one thing at least. In the desert, he would surely have bled to death….

I listened to other tapes. Louis Kalil, to his dying day a devout Catholic, told me how he was finally captured, separated from the rest of his platoon, which hurt more than his wound, and placed on a hospital train on 17 December 1944. The train headed east, toward the Ruhr Valley. His fellow travelers were not fortunate GIs but grievously wounded Germans.

Kalil was not attended to by medics or doctors inside a carriage. Instead, even though his face wound was life-threatening, he was placed between carriages, out in the open, where he quickly felt as if he was going to freeze to death. He had not been given painkillers. As the hours passed and bitter gusts and snow squalls buffeted the train, he became convinced that only God could save him now.

From his blood-stained combat jacket, Kalil pulled out his standard issue pocket Bible and flipped through the pages until he reached Psalm 23.

Blood dripped onto a page as Kalil prayed and then read the psalm out loud so that he could hear the comforting words: “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want . . .”

Kalil read the psalm over and over. It was his only anesthetic. And it worked: he found the strength to keep going through that night’s fourteen hours of darkness and the next morning was able to ask one of his captors for a blanket. “They eventually gave me one,” he recalled. “But I still had no food and no water. I began to get fevers— the bandage from December 16 had frozen onto my face. I hadn’t had it changed. The Germans finally got an interpreter and a German doctor told me I’d gotten gangrene in the wound.”

Kalil knew the Germans would probably not shoot him now. Perhaps they hoped he’d jump off the train and kill himself when the agony of his wounds got to be too much. Another thought obsessed him: How would his parents cope with the inevitable telegram announcing that he was missing in action?

Guards passed where he lay. One kicked him viciously as if he was a lame dog that should have been put down rather than brought along to block the passageways. “After a day or two it was so damn cold I was shivering all the time,” Kalil recalled. “The Germans just kept kicking me. There was nothing I could do. But the worst thing was the teeth embedded in the roof of my mouth. I just couldn’t get them out. Finally, they fell out. Then I felt a little relief.”

Louis Kalil spent the longest winter of his life in various POW camps and hospitals before being liberated by the British today in 1945 and returned to the US in the late summer. He did not want his family to see his badly disfigured face and opted to have surgery before returning home.

After six operations to repair his face, twenty-three-year-old Louis Kalil left the hospital in early 1946 a profoundly changed man. He would take one day at a time and play things safe; he felt he had been blessed to make it home when so many others had not. Like every other returning member of his platoon, all of whom miraculously survived the war, Kalil had a newfound appreciation for family and was determined to spend as much time with his loved ones as possible. When Kalil finally returned to Mishawaka, Indiana, he found his father waiting for him on the front stoop.

“We didn’t know if we were going to have you any more or not,” said Kalil’s father, a look of immense joy and relief on his face. His father dropped to his knees and kissed the ground…

Louis Kalil became emotional for the first time when he told me in 2003 about his homecoming. As I listened to the tape again this morning I could hear his voice drop and the painful pause after he told me about his father kissing the ground.

I now remember looking out of the window into his neat garden back when I interviewed him in 2003. Louis had smiled and had then carried on, just as he had that fateful winter of 1944-45.

“It ain’t too bad.”

That’s what his best friend in a foxhole had told him.

We should all be grateful, for the rest of our days on this overheating globe, that men like Louis Kalil sucked up what life threw at them, carried on, and gave us the freedoms we often take for granted.

There were so many Allied POWs like him in the Stalags today, too malnourished to truly the enjoy the taste of freedom, who had to make do with a few crackers from their liberators’ rations - men who put their lives on the line to save others, defeat fascism, end genocide and restore democracy to Europe.